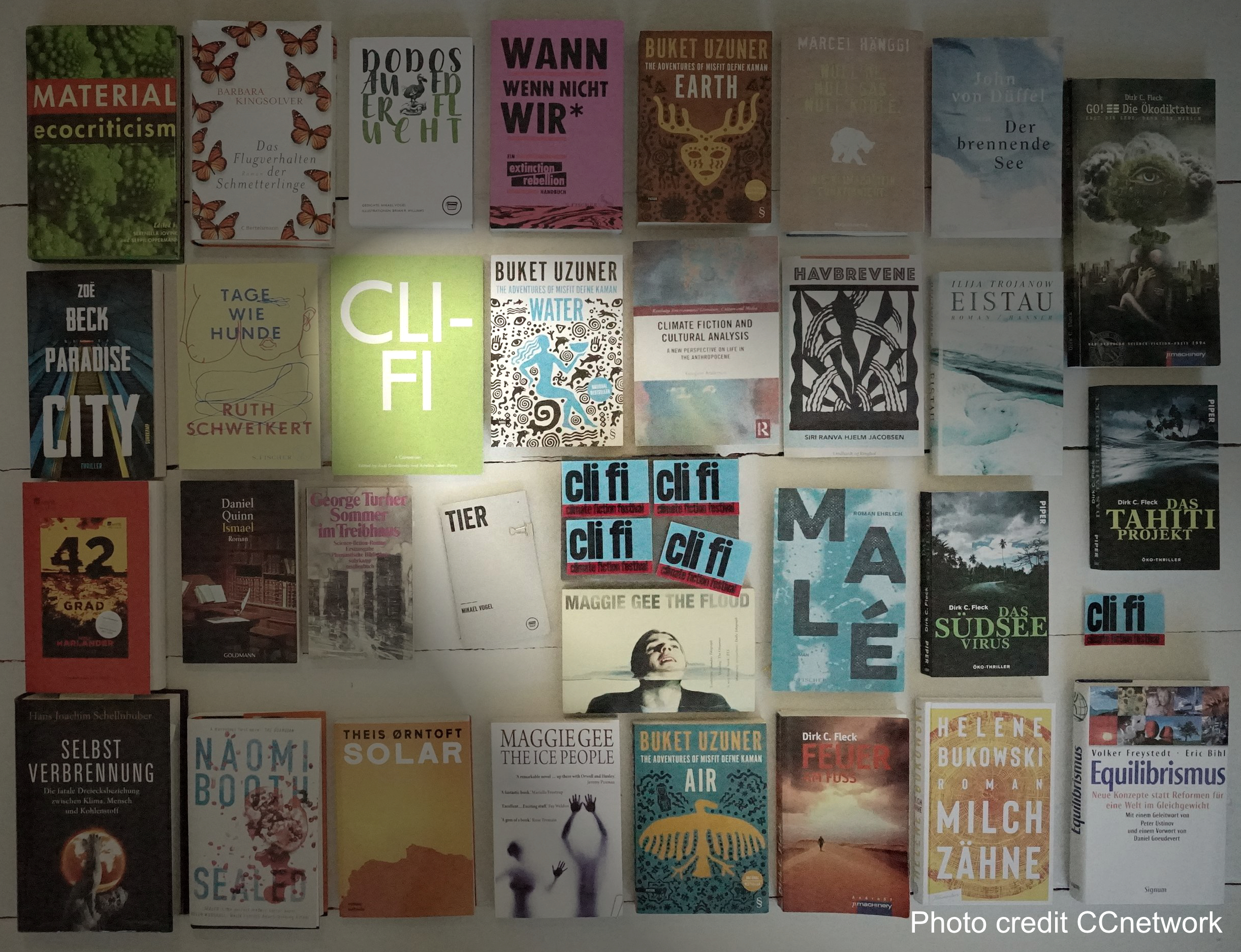

cli fi

Written by Martin Zähringer

Climate Crisis Literature

If an ocean liner is on a collision course with an iceberg, there’s little use in running on deck in the other direction to escape disaster. This image comes from a climate researcher who has been warning us of global warming for decades. Since global warming is steering the earth toward a climate catastrophe, the image of the ocean liner can also be used to describe the situation in contemporary literature: if literature continues to pretend it is not impacted by climate change, sooner or later it too will disappear.

This is why more and more writers around the world are waking up and beginning to ask questions, from a dystopic point of view: is it all over for humankind? Is an eco-dictatorship the only thing that can save us? Or, in a realistic manner: will the climate crisis lead to fascism? What can we do to stop this? How can we take this crisis into our own hands? Or, from a utopic point of view: when capitalism disappears, how will we create a sustainable global economy? Or, combatively: while the world is a dangerous place, literature cannot be benign!

Questions ranging from the dystopic to the utopian, from imaginative to realistic, from speculative to factual, are the basis of climate fiction or cli fi.

Climate Fiction in Science

Up until now, those working in the field of cultural studies have provided the most accurate understanding of cli fi, especially in the interdisciplinary field of ecocriticism. Here, scholars explore the relationships between the environment and ecology, as well as between nature and humankind, as can be seen in older literary traditions such as eco-poetry and nature writing. But where eco-poetry cultivates subjective relationships to tradition and nature writing focuses on nature in the eyes of the individual, climate fiction directly concerns the future and the survival of the collective. Climate fiction seeks answers to the crisis. Political ecology provides a theoretical context for this, and the sociological aspect is central to its literary form.

cli fi is not a trend or genre within the realm of popular literature. Nor is it an esoteric eco-school located on the fringes of the literary world. Climate fiction is narrative literature made up of various genres, from verse to prose poems to multi-volume space epics. Other forms of cultural expression such as film, drama, graphic novels and computer games can be regarded as cli fi so long as they address the same utopian and dystopian themes and narratives.

However, cli fi as an object of research is relatively new. It is only since the beginning of the 21st century that a larger pool of literature has been made available that is worthwhile scientifically. Globally speaking, this pool is now in a state of steady growth.

In 2011, Adeline Johns-Putra and Adam Trexler published the first full-length research article on climate change in literature and literary criticism ( ↗Climate Change in Literature and Literary Criticism). In the abstract, they state: "We explore how the complexity of climate change as both a scientific and cultural phenomenon demands a corresponding degree of complexity in fictional representation." What can be understood from their statement is that a new kind of literature is in the making, and that science needs to react to it with new concepts. This 2011 essay outlined the new field of research that is cli fi.

In 2015, Adam Trexler published the first analytical monograph about climate change in the novel, ↗"Anthropocene Fictions. The Novel in a Time of Climate Change", in which he examines over 150 titles related to climate change. The areas of science fiction, fantasy and speculative fiction were just the beginning of his research for the project. Trexler concluded:

"Climate change is not just a 'theme' in fiction. It transforms basic narrative operations. It undermines the passivity of place, elevating it to an actor that is itself shaped by world systems. It alters the interactions between characters and introduces entirely new things to fiction."

As an umbrella term, climate fiction also rejects the classic distinction between literary and popular fiction. Today, there are many research works, essay collections, anthologies for seminars and monographs on climate fiction; the term is gaining ground.

Axel Goodbody is Emeritus Professor of German and European Culture at the University of Bath. He is one of the founders of the influential European Association for the Study of Literature, Culture, and the Environment (↗EASLCE). Goodbody has been publishing on the subject for decades and especially did pioneer work in the field of ecofiction and climate fiction in German language. 2019 he writes as co-editor of the anthology ↗"Cli-Fi. A Companion" (together with Adeline-Johns Putra):

"Like narrativs of gender identity, the stories told about global warming participate in the organization of our social reality as 'regulatory fictions', deploying metaphorical concepts to define and constitute classes of objects and identities, and thereby determining how the problem is framed. Stories are forms of sensemaking with the capacity to motivate and mobilize readers."

cli fi in the Media

The American journalist and critic Dan Bloom coined the term climate fiction and once explained that, given the relevance of the subject, only this type of literature matters for him now. In an interview with David Thorpe for Smart Cities Dive, Dan Bloom said:

"Cli-fi is still such a new term that only ten percent of the population has ever heard of it, and those novels and movies classified as cli-fi are not on the radar of mainstream book reviewers or movie critics."

On his website ↗www.cli-fi.net Bloom has connected many English-speaking activists from around the world. Today, more authors are writing climate fiction in other languages, but Bloom’s website remains a popular hub for news from the cli fi scene.

Brand-new books in the English-speaking field of climate fiction fall under the expertise of Amy Brady, editor-in-chief at Chicago Review of Books. Since 2017, she has been publishing articles on new climate fiction in her monthly column, ↗Burning Worlds named after J.G. Ballard’s eponymous novel. Most of the content takes the form of author interviews.

Kim Stanley Robinson began the tradition with his science-fiction utopia, New York 2140. The novel follows the struggle between survivors in Lower Manhattan, which lies fifteen metres below sea level, and financial capitalism, which also survived the climate catastrophe. In 2020, Ann VanderMeer writes about artificial intelligence and climate change, David Irvine writes about robotics and climate change, James Bradley writes about ghost species and Charlotte McConaghy, about a journey with the last Artic terns, a rare seabird, and a journey into the inner self.

In German-language media, the perception of climate fiction is just beginning to develop a certain continuity. The literary critics and writers affiliated with the ↗CLIMATE CULTURES network berlin are naturally much more involved in this field. German publishers are keeping up with an increasing number of translations, but new publications written in German are also on the rise.

It is no coincidence that a remarkable number of first-time writers are turning their attention to this topic. After all, the younger generations are much less likely to act indifferently as they are confronted by a perhaps catastrophic future. But they are not the first generation with such a heightened environmental awareness. Franz Hohler already had the end of the world in mind in 1973.

Climate fiction has been around since the middle of the 20th century, apart from some very early examples. Take, for example, the dystopian science fiction novel "Burning Worlds" written by J.G. Ballard in 1962. Noteworthy are also works by Max Frisch (Man in the Holocene, 1980), Ignacio Brandao (And Still the Earth, 2013), David Brin (Earth, 1990), George Turner (The Sea and Summer, 1987) and several works by Ursula LeGuin. These works can all be reread within the context of climate fiction. Especially the American novels can be seen as connected with the early environmental movement and its diverse cultural commitment. The verité artist Tiny Tim warned of climate change as early as 1968.

↗The Other Side (lyrics)

Other well-known works include T.C. Boyle (A Friend of the Earth, 2000), Margret Atwood (MaddAddam Trilogy, 2003-2013), Kim Stanley Robinson (Green Earth, 2015, and many others), Steven Amsterdam (Things We Didn’t See Coming, 2009), Barbara Kingsolver (Flight Behavior, 2012), Jeanette Winterson (The Stone Gods, 2007) and Alexis Wright (The Swan Book, 2013).

Why cli fi?

cli fi is an essential addition to today’s literary canon. It is also some of the most demanding literature, as it responds to the greatest danger we face – the threat of global ecological and civilisational collapse. It is an issue of absolute relevance, which in itself raises a grave question: it cannot be understood in one perfect narrative form. This is why the work of cli fi is not primarily concerned with producing the great climate change novel, but rather with the myriad literary forms in the field, i.e. the literary approach to local issues, events and perspectives.

As readers, though, we can always adopt a global attitude. Anyone looking for climate in literature will find it, everywhere and in various forms. In the past, writers of science fiction, futuristic novels and otherworld fantasies have warned of a terrible future; today, they are recognizing the real crisis. They make climate and critique the focal point of a sincere literature and have become the avant-garde of a new global climate writing.

At the Climate Fiction Festival 2020 in Berlin, we will introduce some of cli fi's European representatives as part of a global movement.